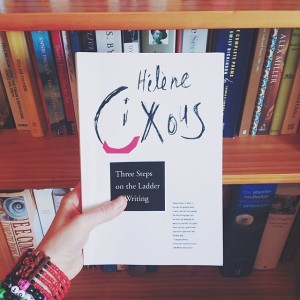

Reading about writing can be something like reading about music. Too meta, too not-quite, too useless. But reading Hélène Cixous’ Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing was an experience I’ve never had before. It’s not a how-to, a craft book, but a philosophy of writing and reading and language, how the three are combined so intimately that we feel it more than know it.

Reading about writing can be something like reading about music. Too meta, too not-quite, too useless. But reading Hélène Cixous’ Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing was an experience I’ve never had before. It’s not a how-to, a craft book, but a philosophy of writing and reading and language, how the three are combined so intimately that we feel it more than know it.

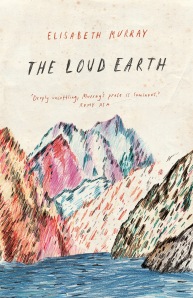

Reading the first chapter, which is actually a lecture, “The School of the Dead,” I felt as if somebody was writing my own unconscious, my own impulse towards writing. She was pulling it out of me. I want to think about how Cixous’ ideas make clear my experience writing my book The Loud Earth and my experiences afterwards, having written it, having others read it. Both were equally strange experiences. “The School of the Dead” took me back to writing the book as if Cixous was transcribing my hours at my desk, which were dreamlike and fast, taken hold of by this story. I felt as if I’d already read this lecture, or heard her speak it, because surely I could not have written something that so perfectly aligns with her thoughts? But I did.

Reading the first chapter, which is actually a lecture, “The School of the Dead,” I felt as if somebody was writing my own unconscious, my own impulse towards writing. She was pulling it out of me. I want to think about how Cixous’ ideas make clear my experience writing my book The Loud Earth and my experiences afterwards, having written it, having others read it. Both were equally strange experiences. “The School of the Dead” took me back to writing the book as if Cixous was transcribing my hours at my desk, which were dreamlike and fast, taken hold of by this story. I felt as if I’d already read this lecture, or heard her speak it, because surely I could not have written something that so perfectly aligns with her thoughts? But I did.

“The writers I love are descenders, explorers of the lowest and deepest. Descending is deceptive. Carried out by those I love the descent is sometimes intolerable, the descenders descend with difficulty; sometimes they stop descending.” She tells us here that literature is meant to be hard. It should not take the easy way out. It should not be pleasant to read, pleasurable perhaps, but not lazy. Sometimes writing flows, I know my pen just moves across the page, I am trying to keep up with the unravelling in my head, but it is never easy.

“The writers I love are descenders, explorers of the lowest and deepest. Descending is deceptive. Carried out by those I love the descent is sometimes intolerable, the descenders descend with difficulty; sometimes they stop descending.” She tells us here that literature is meant to be hard. It should not take the easy way out. It should not be pleasant to read, pleasurable perhaps, but not lazy. Sometimes writing flows, I know my pen just moves across the page, I am trying to keep up with the unravelling in my head, but it is never easy.

Cixous tells us that writing is physical. Descending is a physical motion, you cannot stay where you started. For this reason it’s not just paper and ink. It’s nature, dirt, ocean. “The element (and I would like to have you hear this word said by Tsvetaeva, in Russian: stikhia, she means both the element – matter – and the element – poetic verse – the word element signifies both things in Russian), the element resists: the earth and the sea offer resistance, as does language or thought.” I am interested in the descent literally, I’m interested in the dark places in the earth, the loud earth, that we try to ignore though its calls are sometimes deafening. And I’m interested in the places in our heads and in other people’s heads that are secret, hidden, but important. You can go your whole life ignoring these things. But writers – and readers, how can we separate the two? – must seek these places compulsively. Descend, though it breaks the heart and pushes against you.

This is the ladder she is talking about. Sometimes the ladder is invisible. Which is why writing is like scraping through the darkness thinking you see a flicker of light, then another, and if you’re lucky your path will grow visible, though it’s not a path that was always already there, it’s a path you made, out of the darkness, so you have to turn back to see where you went, where you came from, and then retrace your stumbling. Cixous says, “Giving oneself to writing means being in a position to do this work of digging, of unburying, and this entails a long period of apprenticeship.”

And why is this apprenticeship the “School of the Dead”? Because writing always starts with death. “The [death] that comes right up to us so suddenly we don’t have time to avoid it, I mean to avoid feeling its breath touching us. Ha!” For Cixous all writing is about death. Read a book and think it’s not about death? It’s probably lazy, it probably doesn’t want to dig or unbury. We should be uncomfortable when we are reading. Writing should twist our bodies on the edge of pain. Otherwise we are only avoiding.

“I said that the first dead are our first masters, those who unlock the door for us that opens onto the other side, if we are only willing to bear it. Writing, in its noblest function, is the attempt to unerase, to unearth, to find the primitive picture again, ours, the one that frightens us.”

“I said that the first dead are our first masters, those who unlock the door for us that opens onto the other side, if we are only willing to bear it. Writing, in its noblest function, is the attempt to unerase, to unearth, to find the primitive picture again, ours, the one that frightens us.”

I have been told time and again, “Your book scared me.” “You scare me with your writing.” “Please tell me everything is okay in the end.”

They say it like it’s a bad thing. But why would I write if I wasn’t going to try to dig something out that made you uncomfortable? Why would I skim the surface, then brush the dirt from my palms? If you sit with the discomfort you learn that reading is like witnessing the scene of a crime. “We are witnesses to an extraordinary scene whose secret is on the other side. We are not the ones who have the secret. It’s a pictorial scene.”

We know that art isn’t decoration. It’s not an ornament or gardenscaping. It’s a crime scene. “The duel – death – and the picture form a door, a window, an opening.” Art, in making us afraid, lets us go to places we can never go in reality. But it should be just as petrifying, just as soul-altering, just as physical. Yes, “Writing is learning to die. It’s learning not to be afraid, in other words to live at the extremity of life, which is what the dead, death, give us.”

I write about dead people, ghosts, murder, blood, dark places, deathlust, bloodlust, bodies and secrets. Because “we need to lose the world, to lose a world, and to discover that there is more than one world and that the world isn’t what we think it is. Without that, we know nothing about the mortality and immortality we carry. We don’t know we’re alive as long as we haven’t encountered death: these are banalities that have been erased. And it is an act of grace.”

Which is why I don’t understand “reading is escapism” or “reading is entertainment.” I wouldn’t be alive without language. It’s not exactly a running away. I actually had someone say to me, in response to reading my book, “Well, you know, I don’t really like heavy stuff, I like happy books.”

The point just flew away, unseen, I guess.

Is it about being depressing? Is it about wallowing in sad feelings? For me it’s the exact opposite. Only by reading those writers who don’t turn away, who don’t avoid, who go to the edge and look down that ladder, reach as far as they can, am I able to see what it is to be alive. We need to examine our relationship to the dead. Constantly. And it’s not that by contrast that we’ll know what being alive means to us. It’s because being alive includes death. It includes the dead. As Cixous says, be brave: “Individually, it constitutes part of our work, our work of love, not of hate or destruction; we must think through each relationship. We can think this with the help of writing, if we know how to write, if we dare write.”

Daring to write, to read books that make us lose our worlds, means stumbling through a darkness that is dangerous. Cixous’ concept of the writing process is as perfect as anything I’ve read: “Writing is writing what you cannot know before you have written: it is preknowing and not knowing, blindly, with words. It occurs at the point where blindness and light meet. Kafka says – one very small line lost in his writing – ‘to the depths, to the depths.’” That’s why we know that literature and experience cannot be diametrically opposed, as most people imagine. Have you ever been told you read too much, don’t experience enough of life? Well, quote Cixous next time.

But it won’t be easy. You can’t do it smiling. “Try to write the worst and you will see that the worst will turn against you and, treacherously, will try to veil the worst. For we cannot bear the worst. Writing the worst is an exercise that requires us to be stronger than ourselves. My authors have killed.”

Those of us who are willing to break ourselves at our desks may get close, but it takes strength most of us don’t possess.

“In what is often inadmissible, contrary, terribly dangerous, and risks turning into complacency – which is the worst of all crimes: it originates here. We are the ones who make of death something mortal and negative. Yes, it is mortal, it is bad, but it is also good; this depends on us. We can be the killers of the dead, that’s the worst of all, because when we kill a dead person, we kill ourselves. But we can also, on the contrary, be the guardian, the friend, the regenerator of the dead.”

Complacency may be the worst of all crimes, but it also the most common. Try to talk to anyone about something that runs against the status quo. If you are a feminist you already know this. Most people just don’t want to hear it. But that’s okay. Writing is dangerous. Reading is dangerous. Not the bestsellers, the ones with the masses-approved raised lettering on the cover, but the books that take on this task of befriending the dead.

Complacency may be the worst of all crimes, but it also the most common. Try to talk to anyone about something that runs against the status quo. If you are a feminist you already know this. Most people just don’t want to hear it. But that’s okay. Writing is dangerous. Reading is dangerous. Not the bestsellers, the ones with the masses-approved raised lettering on the cover, but the books that take on this task of befriending the dead.

This is why women writers are not as palatable as men. Black writers are not as market-friendly as white writers. Queer writers may as well bank on a niche readership compared to heteronormative ones.

Perhaps the response to your writing is even more educative than the writing itself. When you are at your desk you will know this is hard, you will know it is dangerous, you will know it makes you cry when you discover that you can turn into language something that crushes your body. But the reaction from people you know once your writing is in print will tell you that you are pushing against the grain every step of the way.

Cixous reveres Kafka.

When she writes about his philosophy of language and literature it’s obvious why, and why he is such a rare writer. He writes about books the way true readers experience them:

When she writes about his philosophy of language and literature it’s obvious why, and why he is such a rare writer. He writes about books the way true readers experience them:

“I think we ought to only read the kind of books that wound and stab us. If the book we are reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow on the head, what are we reading it for? So that it will make us happy, as you write? Good Lord, we would be happy precisely if we had no books, and the kind of books that make us happy are the kind we could write ourselves if we had to. But we need the books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us. That is my belief.”

If the stakes are as high as this for writing and reading, then as Cixous puts it we must recognise that there is “always the same violent relationship: the book first, then you.”

If you experience books like you experience life, sometimes more forcefully, then you will understand this. If someone has ever told you you read too much, that you must experience more of life, as if reading and experience were dichotomous. If you don’t wish to numb that frozen sea inside you, or ignore it.

It is useless to describe a book as happy because it is stupid, because it turns away from that frozen sea, because it doesn’t wound us. As Cixous says, “Those books that do break the frozen sea and kill us are the books that give us joy. Why are such books so rare? Because those who write the books that hurt us also suffer, also undergo a sort of suicide, also get lost in forests – and this is frightening.” But it’s only through this intelligent suffering that we will get true joy, rather than the quick, numbing, fast-food joy of bestsellers or “happy” books, forgotten as soon as you disembark from the plane.

This is why writing begins with death, why it is risky. “The writers I feel close to are those who play with fire, those who play seriously with their own mortality, go further, go too far, sometimes go as far as catching fire, as far as being seized by fire.”

Some people simply don’t experience reading in this way. It is a way of passing time. I don’t know what else. Cixous acknowledges this, though she cannot understand it: “Not everyone carries out the act of reading in the same way, but there is a manner of reading comparable to the act of writing – it’s an act that suppresses the world. We annihilate the world with a book.” Those of us for whom reading is a matter of life and death, sanity and insanity.

We know books are dangerous because we are told so by others every time we pick one up. As Thomas Bernhard wrote:

We know books are dangerous because we are told so by others every time we pick one up. As Thomas Bernhard wrote:

And they call reading a sin, and writing is a crime.

And no doubt this is not entirely false.

They will never forgive us for this Somewhere Else.

This risk means going to crazy places that seem to draw us though we don’t know why. “And for this home, this foreign home, about which we know nothing and which looks like a black thing moving, for this we give up all our family homes.”

On the other hand, if we wish our reading to be numbing, happy-pill, quickly forgotten, we are not like Cixous. She avows: “I have the inclination for avowal. What would the opposite of need for avowal be? The need to remain silent. Does that exist? Do we really want secrets? Real need is on the side of avowal. The true secret causes the most suffering, because it is the exact figure of death. If we have a secret we don’t tell then we truly are a tomb.”

Some days it’s easier to be a tomb. Not to write a lie, exactly, but to not quite write the truth. It’s easy to write out of a tomb, read out of a tomb, the ultimate laziness. But the next day, when we feel some strength or even such weakness that we are newly grotesque and even masochistic, we can cross all of this out and move closer to avowal. Perhaps avowal cannot be done every day, it’s too exhausting. But it’s okay if it’s slow, as long as it’s painful.

Cixous teaches us that while writing is about crossing borders, transcending limits, it’s also about respecting difference. Respecting the things you cannot know. “In life, as soon as I say my, as soon as I say my daughter, my brother, I am verging on a form of murder, as soon as I forget to unceasingly recognise the other’s difference. You may come to know your son, your sister, your daughter well after thirty, forty, or fifty years of life, and yet during those thirty or forty years you haven’t known this person who was so close. You kept him or her in the realm of the dead. And the other way around. Then the one who dies kills and the one who doesn’t die when the other dies kills as well.”

Maybe part of what she is telling us is that there are some things you cannot write. Leave space in your writing. That’s a hard thing to accept. We want to write everything, we want our characters to know each other deeply, we want to know our characters deeply, we want to put our sons, our sisters, our daughters into our writing as if we have a hold of them. I think here of Levinas’ notion that the other is always unknowable.

Though his writing his utterly sexist, positioning the feminine as the mysterious other, denying any form of feminine subjectivity, and giving a whole new meaning to the male gaze, difference is important to consider from an ethical perspective. In my book the narrator wants to collapse all difference between herself and Hannah, because it is too painful to accept her borders, which explains her deathlust and how ultimately destructive it is to be possessive of another person without really seeing them. Cixous knows that if you don’t see the other person, only yourself through them, you are verging on a form of murder. The narrator takes this literally.

Though his writing his utterly sexist, positioning the feminine as the mysterious other, denying any form of feminine subjectivity, and giving a whole new meaning to the male gaze, difference is important to consider from an ethical perspective. In my book the narrator wants to collapse all difference between herself and Hannah, because it is too painful to accept her borders, which explains her deathlust and how ultimately destructive it is to be possessive of another person without really seeing them. Cixous knows that if you don’t see the other person, only yourself through them, you are verging on a form of murder. The narrator takes this literally.

My narrator is haunted by the crime scene of her murdered father and stepmother. Did she do it? She cannot think it to herself, so we have to think about it ourselves, as the reader. Cixous offers an explanation: “the loved one remained inside her, a dead man inexplicably without his death.” When we write, when we call up the dead like this, we are calling up a whole set of confusing feelings that are difficult to separate: what is his? What is mine? “She is staging an unenvisionable crime. What she lives out, and what she rejects with all her strength, is the fact that the deadman reproaches her for being alive. This is something she cannot come to terms with since she is both characters at once, herself and her-him. She is guilty of being a survivor. She didn’t follow him. She isn’t him.”

This works if she was the murderer and it works if she is. I don’t know why I am drawn to texts with this “unenvisionable crime,” these unresolved crimes. Perhaps because as Cixous claims “all great texts are prey to the question: who is killing me? Whom am I giving myself to kill?”

This is why great texts are like crime scenes, so much is at stake. “What finally emerges from the earth of the narrative is that we need the scene of the crime in order to come to terms with ourselves: we need the theatre of the crime. We need to be able to expose the crime and at the same time to somehow keep it alive.”

But this ain’t crime fiction. Because it is unresolved. The social order is ultimately left in the mess we began with. The lack of a resolution is the same as what is in the mind of the narrator. Full of illusions, delusions. “This is how we regulate our way of not seeing, or seeing what we don’t want to see. Seeing, not seeing, making visible, hiding/exposing, what? What is there in that heavy bag he is carrying?” I think this is one of the things people resist. But this is where intelligence resides: to accept the mystery, but to want to know. Desire and murder at once. A few people have asked me “What happened? Did she do it? Did she kill her parents? Did she kill Hannah at the end?” I do not want to answer. For one thing I don’t know. But my favourite thing is when people discuss the possibilities, and are not afraid.

A resolution is tempting, but it isn’t possible. “The inclination for avowal, the desire for avowal, the yearning to taste the taste of avowal, is what compels us to write: both the need to avow and its impossibility. Because most of the time the moment we avow we fall into the snare of atonement: confession – and forgetfulness. Confession is the worst thing: it disavows what it avows.”

But in one sense don’t we have to be afraid? Because reading isn’t “over there.” It is also inside me. Cixous sums up this conundrum: “Dostoyevsky was prey to this character’s mystery: what causes a young woman to bloody the entire house. She is a monster who isn’t a monster. I could be her. I am also you.”

We want to keep intact the other’s difference but we know it is not always possible. In the end Levinas’ idea of radical alterity is not satisfying. Irigaray does a better job, explaining that difference isn’t an opposition, it’s a possibility for creativity.

Imagine a Western concept of the body in comparison to the Eastern concept. The body is bounded in Western thought, in opposition to other bodies, whereas in Eastern thought it is subtle, the bounds of the self aren’t so easily defined, relationality becomes more complex.

Imagine a Western concept of the body in comparison to the Eastern concept. The body is bounded in Western thought, in opposition to other bodies, whereas in Eastern thought it is subtle, the bounds of the self aren’t so easily defined, relationality becomes more complex.

Writers know that our bodies are subtle even if it’s only an unconscious knowing. Because books have subtle bodies. One person wrote them, quite another person reads them. “The author writes as if he or she were in a foreign country, as if he or she were a foreigner in his or her own family. We don’t know the authors, we read books and we take them for the authors. We think there must be an analogy or identification between the book and the author. But you can be sure there is an immense difference between the author and the person who writes; and if you were to meet that person, it would be someone else. The foreign origin of the book makes the scene of writing a scene of immeasurable separation.”

Writers know that our bodies are subtle even if it’s only an unconscious knowing. Because books have subtle bodies. One person wrote them, quite another person reads them. “The author writes as if he or she were in a foreign country, as if he or she were a foreigner in his or her own family. We don’t know the authors, we read books and we take them for the authors. We think there must be an analogy or identification between the book and the author. But you can be sure there is an immense difference between the author and the person who writes; and if you were to meet that person, it would be someone else. The foreign origin of the book makes the scene of writing a scene of immeasurable separation.”

And if the book is out there, mine, written by me, it is also inside you, read by you. “This turbulent landscape is our inner storm, it’s the curtain-raising of the unconscious. The world is white, we are lost, a great wind blows, and there in the background is a small black spot. We wonder what it is.”

Writing, and reading, are ways to communicate with the other, to experience the ways that our bodies are in fact subtle. Because literature is also physical. “These people have taken us through the storm ‘toward the depths’ where we can’t see clearly what we see, to discover ‘the most known unknown thing.’”

So it’s strange when somebody tells me “You scared me with your book.” Did I? I am not quite the person who wrote that book. Writing is another mode of communication altogether. We simply do not communicate with people in the same way as we write literature. That is why we need it so badly. And those who ask me for “the answer” to the book, as if there is one? I did not write the same book that you read.

If you love writing, if you love reading, if you find literature is the only way you can make sense of the world – and even more than that, the best way to make sense of the world – you must read Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing. Cixous has written this book with your blood.